12-11-2015 | According to the Waste-Free Kitchen Handbook, everything can be saved from the garbage—even sour milk.

If food waste was a country, it would be the third largest emitter of carbon pollution in the world (and a horrible place to live). Vast amounts of energy go into growing and delivering and refrigerating food—and then, in places like the U.S., around 40% of it ends up in the trash.

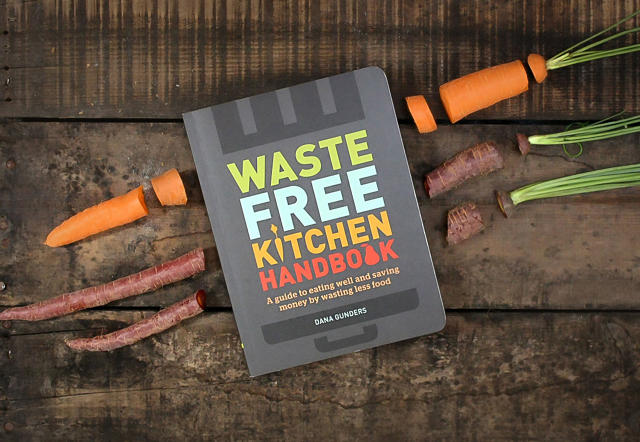

A new book, the Waste-Free Kitchen Handbook, explains how you can stop throwing out food at home—where you’re probably part of the problem:

Collectively, consumers are responsible for more wasted food than farmers, grocery stores, or any other part of the food supply chain. The lettuce that went bad, the leftovers you never got around to eating, and that scary science experiment in the back of your refrigerator—it all adds up.

Dana Gunders, a staff scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council, wrote the book after a long obsession with food waste. She originally researched ways to help improve farming—saving water, fertilizer, and pesticides, and land—and then realized that slowing food waste could have an equally large impact. If the U.S. could reduce food waste by a third, it could also feed every food insecure person in the country.

Saving food isn’t necessarily hard, Gunders says, and it doesn’t require any new technology. But we now waste 50% more food than we did in the 1970s. So the book is a cleverly-written reminder of all the things your grandmother probably knew how to do, from saving burned food and pickling vegetables to what you can safely feed your dog (or chickens) if all else fails.

Here are a few of the suggestions:

1. Plan, and then stick to your plan

That slimy spinach you’re scraping into the trash might have started with wishful thinking—maybe you got inspired by the Food Channel and then got too busy or tired to cook, or decided to go out to eat, or just didn’t feel like whatever it was you wanted to make. Maybe you bought too much. The single biggest way to throw out less food, Gunders argues, is to plan meals in advance. The plan should include a dose of reality—if you’re probably going to be too lazy to cook on Wednesday, don’t buy ingredients you won’t use.

2. Take a food waste audit

For a couple of weeks, keeping track of everything that goes in the trash can help you figure out where things could change in your routine. The audit should also include why—you bought too much, you felt like watching TV instead of cooking—and an estimate of how much you spent on it. You might notice that some things get wasted more than others; Gunders notes that the biggest things to focus on reducing are meat and dairy, since they have the most impact on the farm.

3. Optimize your fridge

Few of us actually know why a cheese drawer exists or how crisper drawers work, so Gunders explains. The back of the book also includes a detailed list of exactly how and where to store foods so they last longest. One of the biggest lessons: The lower shelves in a refrigerator are a little colder, so they’re a better place for the things at biggest risk of going bad. Nothing but condiments should go in the door, the warmest place in a fridge.

4. Keep your sour milk

Some things are pretty harmless to eat, like brown spots on bananas—or sour milk, as long as it’s pasteurized. If you can’t handle the taste, Gunders includes a recipe for pancakes that replaces buttermilk with sour milk. The book also outlines why “use by” and “best before” dates are mostly meaningless, and how to tell whether something’s going to kill you.

5. Freeze anything

If you’re going on vacation and didn’t finish your food, pretty much everything in your fridge can go in your freezer. Same goes for leftovers or ingredients you aren’t ready to use. The book explains how to prep everything so it doesn’t end up soggy or otherwise unappetizing, and charts the best way to pack the freezer.

6. If all else fials, compost

Composting is a last resort, after freezing and feeding pets whatever they can safely eat. But because food pumps out methane—a potent greenhouse gas—in landfills, composting is a whole lot better than tossing food in the trash. Gunders suggests putting a compost bucket in the freezer if the smell is a problem.

The book also includes a full section of recipes, like how to saute wilted lettuce or infuse old fruit into vodka, and dozens of other detailed but simple suggestions, all backed up by research. And though the writing is never sanctimonious, it’s always clear what the impact of food waste is—and why we need a change. As Gunders writes:

“It’s actually very simple. We just need to value our food. Just imagine operating under the belief that food is a really important, valuable asset that takes huge amounts of resources to produce and is in fact critical to our survival. And that because of this belief, it really isn’t okay to just waste it. What would that look like?”

Source: Fastcoexist